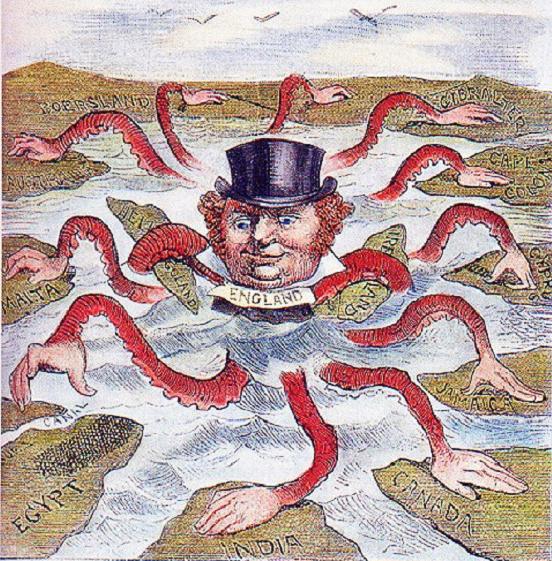

Countries Preventing the English Language Invasion

Photo via Wikimedia

Thanks to the internet, it seems that English really is everywhere. It sneaks into our vocabulary without even really trying, with loanwords for the things we take for granted becoming the norm, even in countries whose first language isn’t English. The question is, is it always welcome? Are non-English speaking countries happy with their hashtags, weirded out by their Wi-Fi, or ecstatic about their ethernet cables?

Apparently not.

For some, English isn’t the be-all and end-all, at least for those who dislike the idea of the English language invading their own. Let’s take a look at some of the countries who would rather English didn’t sully their tongues at all.

Turkey

First on our list of not a fan of English, is Turkey’s president, Recep Tayyip Erdogan. In May 2017 he declared:

“Where do attacks against cultures and civilisations begin? With language.”

And a brief look at the history of the world would show that at least in some ways, he isn’t wrong. The first word to publicly meet with Erdogan’s disdain was arena, likening it back to ‘ancient Roman depravity’, demanding its removal from sports venues overnight. Besiktas football club’s home ground went from Vodafone Arena to Vodafone Stadyumu in the blink of an eye. The origins of the word stadium was generally an oval or horseshoe-shaped structure where spectators could watch sports, namely foot races, but arena has its roots in more dubious activities, for example gladiator shows and other barbarities. Erdogan, then, has a very good point.

Other English words that have advanced on the Turkish language are things such as atasman (attachment), trafik (traffic), and teras (terrace) – although those last two could be seen as a French influence rather than an English one, since French loanwords account for around 5% of Turkish vocabulary. Either way, Western nouns arrived in the Turkish language in the 19th century owing to trade, but it seems they might have outstayed their welcome.

Photo via Pixabay

China

If there is one language that can truly complain about the invasion of English into their language, then surely it is Mandarin, closely followed by Cantonese. Western words have crept into the logographic systems of these languages; where once these hànzì characters were drawn to represent the thing they were talking about in a visual way, more modern characters simply reflect the sounds they make to fit in with Western words.

In 2010, all newspapers, publishers, and website-owners in China were banned from using foreign words, especially those in English. This included foreign abbreviations and acronyms, as well as the so-called ‘Chinglish’ hybrid of English and Chinese. The government cited the damage of the Chinese language as the reason for the ban, allegedly fearing the social implications.

Since then, there has been a blanket ban on all foreign media from publishing in China without express permission, and there are strange tales of things like any mentions of Winnie the Pooh being classed as illegal across all of China’s social media. We understand, perhaps, the need to protect a language from bastardisation, but what did Winnie the Pooh and any of his friends in the Hundred Acre Wood do to anyone?

Photo via Pixabay

France

Oh, but how some native French speakers loathe the abomination that is English. In the past there have been fears from the French that any influence of English would water down the French language, perhaps even threaten it to extinction, though we can’t imagine that ever happening; French is a beautiful, rich language with so much heritage and importance, that we can’t imagine a time in this world without it – nor do we want to.

But France, and not all French speakers, we should clarify, does take offence at the presence of English in its world. Back in 2013, the word hashtag was banned altogether and replaced by mot-dièse on Twitter, this word itself being of Gallic origin and meaning ‘sharp word’. This ban has now been lifted, but the debate is still there.

Learning a new language? Check out our free placement test to see how your level measures up!

Other words that might make someone’s eye twitch are things like le jogging, le week-end, and les cheeseburgers, so we can’t exactly blame the internet for that because these aren’t new words. But since the internet, there has been a tendency to shove the French ending er on to a lot of English words instead of making new ones, examples of which are skyper, tweeter, forwarder, and liker, which we are fairly confident don’t need any kind of translation. There are even horrific things such as dans l’open space and relever le challenge, and it’s easy to see why some of these things make the good French folk cringe.

We have barely scraped the surface of what English-isms are simply unacceptable in other languages; what are your favourite ones to hate?