Getting þorny with Old English

You did a double-take there, didn’t you?

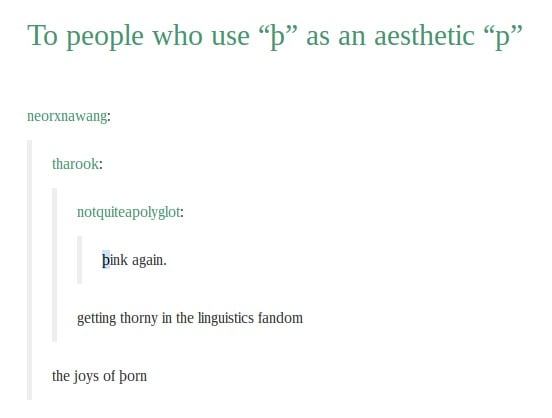

Whilst we hope we won’t be accused of click-baiting you into reading this article, we are happy to have enticed you in. Hello! And if you’re a frequenter of social media, it’s likely you’ve seen this letter in use in all manner of incorrect ways (along with other letters, obviously). For example:

Which, if you’re Icelandic, a linguist, or, you know, have eyes, might set your teeth on edge.

What we’re talking about, of course, is the aesthetic use of Old English letters. Because if you’re going to start a resurgence in Old English, we want you to be sure you know what you’re actually saying.

A brief history:

English has worn many guises over its time. Old English, or Anglo Saxon, happens to be, well, the oldest incarnation of the language. First brought to Great Britain by Anglo-Saxon settlers sometime in the fifth century, Old English was spoken in England and parts of Scotland up until the Middle Ages, over a period of about 700 years.

Photo via Giphy

Old English can be divided further into Prehistoric, Late, and Early Old English, and you can be sure that just as with Modern English, there was a smorgasbord of dialects to confuse people from different regions, though these were roughly split under the headings of Mercian, Northumbrian, Kentish and West Saxon.

Back to the letters

Yes, (^^^) this does indeed make a ‘cuter’ smiley face (…), and we’d like to state for the record, that we are just as voracious a user of emoticons/emojis as anyone else. When we’re talking about the letter þ being used in place of a p, it gets us upset. We’re all for expanding our language horizons, even if it does involve a step back in time, because language is beautiful. But please; would you use it correctly?

Thorns?

Þ, pronounced th, if you didn’t already know, went out of circulation as an English alphabet letter with early printing presses, whose fonts were imported from places like France, Germany, and Italy, where no þ existed, and therefore came to be replaced with a y. This is where we get things like Ye Olde Tea Shoppe, because the y here is in fact þ.

…and?

Okay, so perhaps it’s not a big deal, but we don’t like it. However, since we’re on the subject of and, did you know that &, or ampersand, used to be an actual, bonafide letter of the English alphabet as well? Now it might be used to save character space in our Tweets, but this little letter once was used as part of everyday cursive script.

Learning a new language? Check out our free placement test to see how your level measures up!

Now, the symbol & actually predates the word ampersand by some 1500 years. Roman scribes linked the letters e and t – the Latin word et of course predating the English and, and over time, this letter came to be part of the English alphabet. Children in the 1800s would recite the alphabet, finishing it with and, or per se, meaning by itself, and over time and per se and became ampersand, ampersand became and, and we all got very lazy. So technically, & isn’t a poorly-used Old English letter; but it’s important to know our history, don’t you think?

Now, onto the others

Photo via Giphy

We promise, we do have other examples:

Æ, or ash, used to represent a Latin-origin diphthong, is a good place to start. Words like archaeology used to be spelt as archæology, meaning in theory even the modern æroplane could have an Old English twist. Æ itself originates from the rune œ before English became Latinized, and is still in use in languages such as Icelandic and Norwegian; so what we’re saying is use it, but use it well.

Ŋ is an example of an Old English letter that actually might be useful today. The eng letter is used to represent the nasal sound of n and g together; sing would become siŋ, for example, though we can imagine an aesthetic use of this to write the word sin, and we are not amused.

And finally: ⁊, or ond, is not a stylised number seven, but rather an old form of shorthand for scribes. Ð isn’t a decorative d, and instead is pronounced eth. And though this might be a reach, since linguists debate the presence of the ß as a replacement for ss in Old English – yes, we know it is esszett in German for that exact purpose – never ever should this letter be aesthetically placed instead of an s. Here’s why:

So! We hope we’ve amused you with our brief look at some misused Old English letters; next time, we will look at Old English words that potentially are due a comeback. Until then..