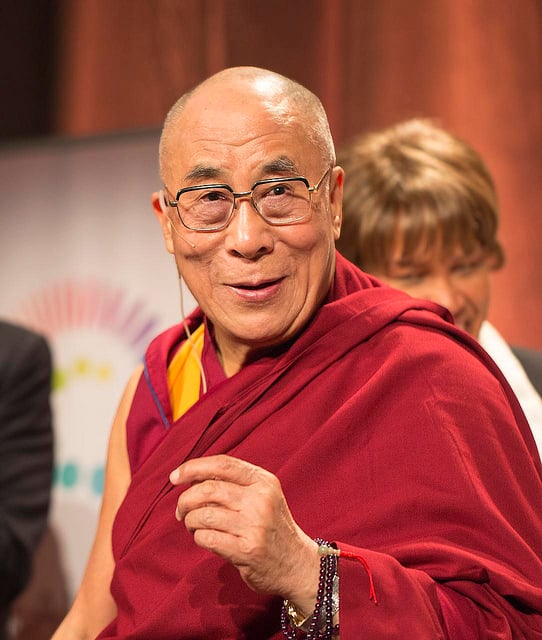

The Dalai Lama Says ‘Let Them Drink Horse Milk’

Photo via Flickr

If any of you are familiar with American NPR, at some point, you may have been witness to a few headlines celebrating the Dalai Lama’s many messages. More recently, a headline read ‘Dalai Lama says he cured Mongolia of alcoholism by promoting drinking horse milk.’

Now, it’s not unusual to find peculiar story lines attached to his Holiness. Just a quick search on NPR’s own site brings up, ‘Dalai Lama prefers badminton over golf, has never seen caddyshack’, or ‘Dalai Lama backs digitally mapping human emotions’, and ‘Dalai Lama may choose not to reincarnate’.

As you can tell, the Lama is in the news a lot, venerated internationally as a spiritual leader and tireless campaigner for human rights. He is definitely a much loved figure, but did he really cure Mongolia of drinking vodka?

The story comes from an interview by the host of Last Week Tonight, John Oliver. Oliver travelled to Daramsala, India where the exiled Tibetan leader lives among thousands of his followers who fled when China invaded and claimed sovereignty over Tibet. During the interview touching on mostly political points involving Chinese oppression the Dalai Lama dropped this non sequitur about his suggestion to the people of Mongolia. ‘Drink less vodka, instead drink horse milk… and they follow, they follow what I’ve said.’ Oliver received this with a little consternation and a lot of horror at the thought of drinking horse milk.

Learning a language? Check out our free placement test to see how your level measures up!

Airag is the traditional alcoholic drink of the nomadic people who lived across the central Asian plains. It’s essentially fermented mare’s milk with an alcoholic level equal to hard cider. Airag more often known by its Turkish name Kumis is an alcohol in its own category being fermented from milk as opposed to either fruit or grain. Served cold or chilled it has a sour taste with an after bite from the alcohol and is consumed all over central Asia in one form or another. It seems, though, that what the Lama was suggesting was that people return to their roots and leave the high octane vodka alone.

Photo via Pixabay

Why he brought this comment up that he made during a 1995 visit to Mongolia in a 2017 interview was probably to enhance the humour; Last Week Today is a comedy show and John Oliver’s reaction to the story is the funniest part of the video, but the concern of alcoholism is not a dead issue. Tsakhiagiin Elbegdorj, the current president of Mongolia has been making similar suggestions since 2011 and credits the Dalai Lama’s statement as having a big influence on people’s decision to either lessen or give up drinking.

According to a WHO (World Health Organization) survey only about 38% of Mongolians reported having a drink in any given month. This is low compared to America where 56% of people report having at least one drink per month. This apparently shows a drop in the percentage of drinkers in Mongolia over the last ten years.

My experience in Mongolia didn’t really back this up, though. There was a lot of drinking and encouragement to drink. Mongolia has a toasting tradition much like China’s and less so than Thailand’s. Dinners are punctuated with lots of very short speeches and bottoms-ups, mostly of cheap vodka, but for the older and more adventurous there was airag. When I asked my guide and translator about trying it, he made it clear what he thought about the effects it wold have on me by squatting, making a painful face and then mimicking vomiting between his legs. An acquired taste it seems.

In the end neither the Lama’s plea nor the president’s probably has had much effect on the people I saw walking around in stupors or the youth who passed bottles of super cheap vodka around as they hung out on the streets of Ulaanbaatar. At least though he made that plea, like many issues the Lama turns his attention there is not an immediate effect but his words spread and eventually lead to change.