From Hieroglyphs to Emojis: Maintaining a Visual Presence

When we think of cultures using pictograms, a visual representation of a person, place, or thing, and ideograms, a visual representation of an idea, we tend to think of ancient cultures, right? Sketching on a cave wall or in the dirt to pass on information to the next generation of the tribe probably started soon after homo-sapiens came down from the trees. Just as imagery shows up all over the ancient world, on every continent dated back to the dawn of civilisation, pictures were used to tell stories, and now it seems have come back in a pretty outstanding way.

Photo via Flickr

Some anthropologists will argue that it is the development of complicated language, not the development of tools, that separate man from beast. All animals have the ability to communicate, to warn off predators, to attract mates or to teach their young how to survive in the dangerous world they’ve been born into. However, it’s only humans, though, who write these things down. It could have been one of the advantages that homo-sapiens had over Cro-Magnon men that allowed us to take over and run them off the planet.

Picture or language?

Not all ancient images can be considered a language. Some seem to have been made either to commemorate an event or as a way to worship as opposed to communicate an idea for posterity. The famous caves of Lascaux in France are decorated with hundreds of easily identifiable animals both living and extinct. The paintings were done by generations of inhabitants who left hand prints as signatures along the walls, however, based on their composition, the images were probably done to celebrate and give thanks for successful hunts.

Photo 2.

Learning a language? Check out our free placement test to see how your level measures up!

In contrast, a group of obelisks that date from around the same time, 15,000 years ago, in Gobekli, Turkey also features groups of animals: birds, scorpions and humans, but composed in a way that they are meant to be ‘read’ in a certain order to pass on information. Altogether the site seems to be a star map and many of the pictograms illustrate the changing seasons and movement of constellations in the night sky. This recent discovery is possibly the earliest example of pictorial language.

Photo via Wikimedia

Modern pictograms

Generally that is the assumption: pictorial language is ancient or carried on only in non-literate cultures, but in fact images as language have never gone away in any culture, ever. Think about it. In many cases it’s easier to get the message across using a stick figure or symbol as opposed to a group of words. Imagine the figures of men and women to designate restrooms, the skull and bones warns of danger and the thumbs up shows approval.

But that’s just the beginning!

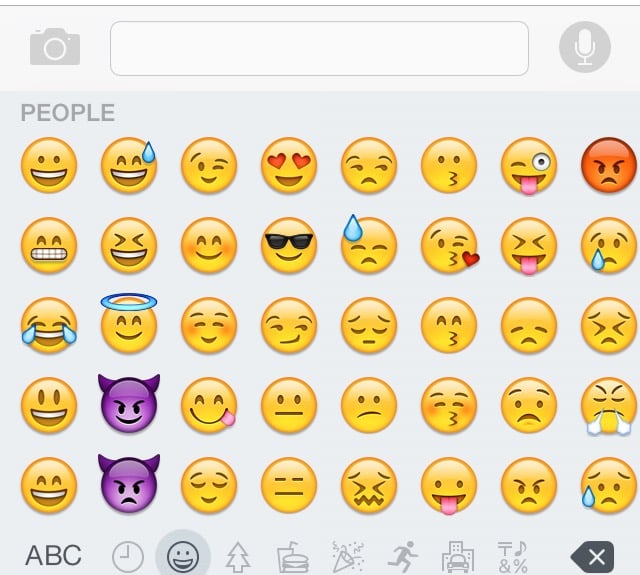

Today, the emoji is an almost omnipresent language of images that makes passing on the quick judgements that fuel social media fast and easy. They break language barriers and span age differences. Though the emoji arguably lacks the sophistication of Egyptian hieroglyphics, which acted as both pictogram and phonetic language, emoji users practise the shared knowledge of conveying complex ideas with fluffy poodles, martini glasses and peaches that make up that alphabet.

Really though, this is nothing close to a dying art. Look at any piece of technology and you’ll suddenly start to realise the lack of words, but instead dozens of visual representations, whether you want to make a phone call, open your e-mail or even check the weather. Images have always been a part of communication and with the lack of verbal communication, will only become more prevalent. Problematic? Efficient? Annoying? Helpful? We’ll have to let you decide.