Chinese: A Breakdown of the Writing System

They say you can learn a lot about a person from their handwriting. Graphologists suggest that they can interpret emotions, mindsets and even environments, just from studying someone’s scrawl.

So what about writers of Chinese? Is the same true for them?

We’re more about the language and less about the writing if we are being honest, and that has nothing to do with our own poor efforts at good penmanship. We promise. So let’s take a look at the frankly mind-boggling array of writing forms that can be found within the bracket of the Chinese language.

A quick introduction

Table of Contents

Photo via Wikimedia

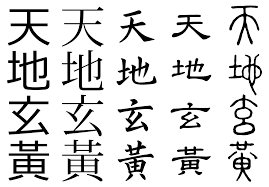

It is thought that the Chinese writing system was developed as early as the Shang Dynasty, around 14 BCE. These first characters were found carved into tortoise shells and pieces of bone, hence some of the earliest examples being referred to as oracle bone script.

The written form of Chinese is universal; it is the way the words are spoken that generates all the different varieties of Chinese – and other related languages – that we recognise today. Each individual character corresponds to one meaningful unit of the language rather than to an idea or thought, which is how Chinese writing was originally interpreted.

According to the traditional theory described in the dictionary Shuowen Jiezi, Chinese writing can be explained using Liu Shu – 六书 – or, the six writings.

Xiangxing 象形 – Pictograms

Pictograms are characters that tend to have originated from drawings of objects. Think of these as less of a picture and more of a rough sketch of an object that has over time evolved into a character representing what are essentially nouns today.

Some of the ideas behind the pictographs have more thought behind them than you would imagine at first glance. Our example here is 人, which in pinyin is rén and means person. This pictograph has evolved over time and is shown to represent the idea that people need people because people prop each other up. See the way the two arches curve together?

Learning a new language? Check out our free placement test to see how your level measures up!

Zhishi 指事 – Indicatives

Zhishi originates from the words point and matter, coming together to generally express things that ‘point to the matter’. There are two ‘subtypes’ of these characters, one composed of a pictograph and the other of an indicating sign.

Here’s our example. 本 is gén, meaning roots. This word is comprised of 木 – tree and 一 – which is drawn at the bottom of the ideogram to indicate the base or roots of the tree. If you think that’s a little confusing, be glad we didn’t attempt to explain an abstract ideogram! Indicatives form the smallest fraction of Chinese characters, simply because there are easier ways to express composition.

Photo via Pixabay

Huiyi 會意/会意 – Ideographics

These characters are what can be thought of as ‘logical aggregates’, in that they use two or more parts to express their meaning. This can either be displayed as characters side by side or on top of each other.

To demonstrate, take a look at 明 – ming, which is brightness. The two characters used to depict this character are taken from 日 – sun, and 月 – moon, two objects that always appear brightly in our sky – an obvious choice. We doubt it is a coincidence that this word is also used to describe one of the most successful Chinese dynasties – the Ming Dynasty.

Xingsheng 形聲/形声 – Phonetic compounds

These characters are also two-parted. We have the radical, which is the graphical or semantic component of the character, and the phonetic component. Take care when using these characters, because they give a general meaning rather than a specific explanation.

Let’s take a look at how this one works. 晴 is qíng or clear/fair weather. To express this, we have 日 – sun, and 青 – ‘blue/green’, which is used for its pronunciation.

These characters make up the majority of characters within the Chinese writing system and demonstrate how important it is to know the sound elements of Chinese words.

Zhuanzhu 轉注/转注 – Mutual explanatory or Transfer

These are characters that have a concrete, simple meaning yet usually take on a more abstract one. Similar to Xingsheng, to produce Zhuanzhu tends to involve two or more characters. Some of the components of these words share the same semantic radicals, and therefore can in fact explain one another. Others show clear transference, where one concept has become to mean something else entirely.

Transference examples are more logical to explain, so let’s take a look at one of them. 網/网 or wǎng means net, which can be seen quite clearly because the original pictogram depicts a fishing net. Maybe if you squint. However, in everyday speech, this has come to represent a computer network. Which is pretty clever if you think about it.

Photo via Wikimedia

Jiajie 假借 – Phonetic loans, or borrowing

Simply put, this category of characters is those that use existing characters in a new, alternative way to their original meaning. Characters are used, either accidentally or intentionally, for entirely different purposes, often until new characters are created.

Our example here is 哥 or gē, which means older brother, and uses a character that used to mean ‘sing song’. Sing song is now written as 歌, but is also pronounced gē. What has happened here is that a character with exactly the same pronunciation has been used, or borrowed, until a character for older brother came into existence. Which sounds both complicated and clever to us.

Photo via Wikipedia

And we’ve barely scratched the surface…

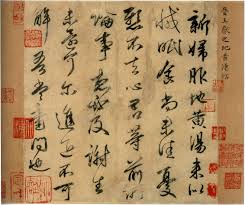

Because we haven’t yet talked about the strokes that form the characters, the direction of writing, the layout, and the various styles of writing within the bracket of Chinese writing. Since Chinese is one of the oldest continually used writing systems in the world, it really should come as no surprise that there is so much to learn about this fascinating language.

So, if you’re truly committed to learning Chinese and want to boost your writing and reading skills in this language, you will probably need the help of an expert native-speaking Chinese teacher. To find the best one, explore our list of face-to-face and online courses and begin your journey towards being fluent in Chinese!